There's never a good time in college football to have a bad season, but 2025 would mark a particularly bad time for Brent Pry and his Virginia Tech Hokies to have a bad season.

Pry carries a 16-21 overall record and a 10-13 mark in ACC play heading into his fourth season, but his three seasons to this point don't so much signify a downturn as much as they are a continuation of a new normal in Blacksburg. After winning 19 games in his first two seasons of 2016-17, Justin Fuente's teams finished below .500 in 2018, 2020 and '21. At a program that won seven Big East or ACC championships from 1995-2010, Virginia Tech is now 14 seasons removed from its last conference championship and eight years removed from its last title game berth. When the Hokies last played in a major bowl game, the opposing head coach was Brady Hoke.

In short, the times have changed, the toll to thrive in major college football has risen, and Virginia Tech has been unwilling or unable to pay it.

And so next week, Virginia Tech AD Whit Babcock will make his case to the school's board of trustees (they call it the Board of Visitors at VT) that the school needs to commit $52 million in new investments in order to return to the top-tier of the ACC. Though the presentation is not until Aug. 18, the materials he'll use to make his argument are already online, and he's already spoken to the Virginian-Pilot about the Hokies' situation.

“For us it’s really simple,” he said. “We need to get better (in football) because the better you do, the more money you get from the ACC. So, the recipe is still the same. Be really good in football. Be good in some of your other sports. Don’t operate under scandal and have very good academics. But yes, there’s a sense of urgency in the near-term.”

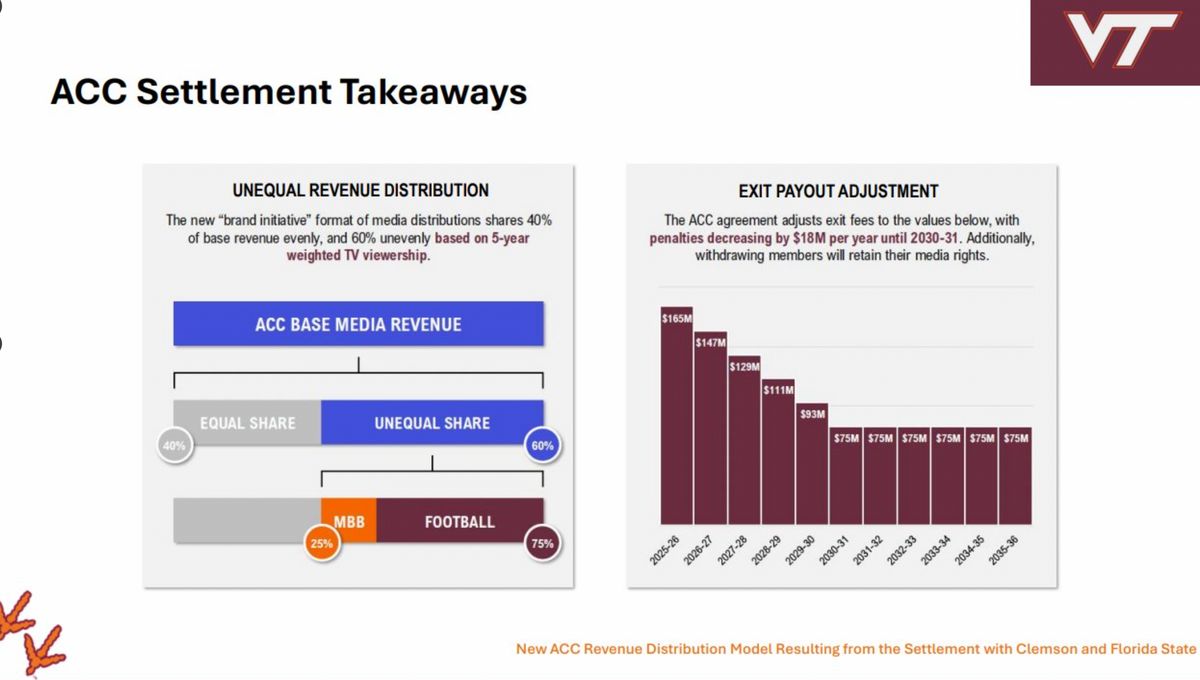

That's because, in order to pacify Clemson and Florida State, the ACC has altered its revenue model to essentially create a haves and have-nots within their own conference. Moving forward, 40 percent of the conference's money will be split equally among its 14 "legacy" schools, and the remaining 60 percent will be awarded to the teams that play in the highest-rated games.

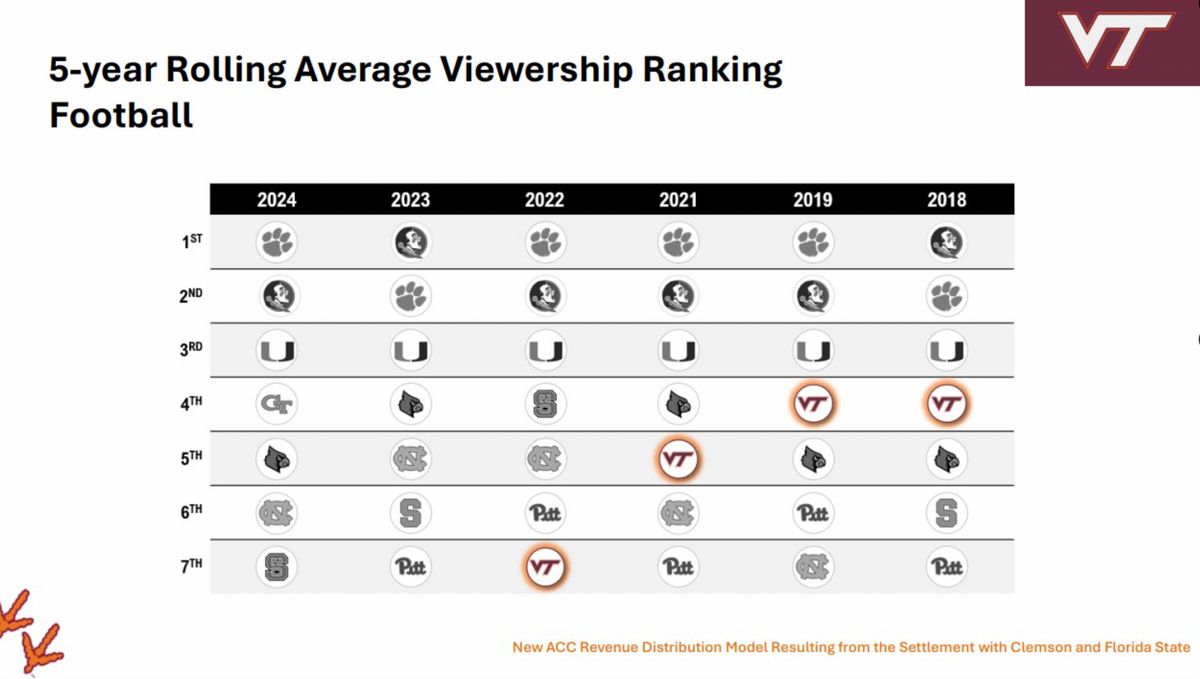

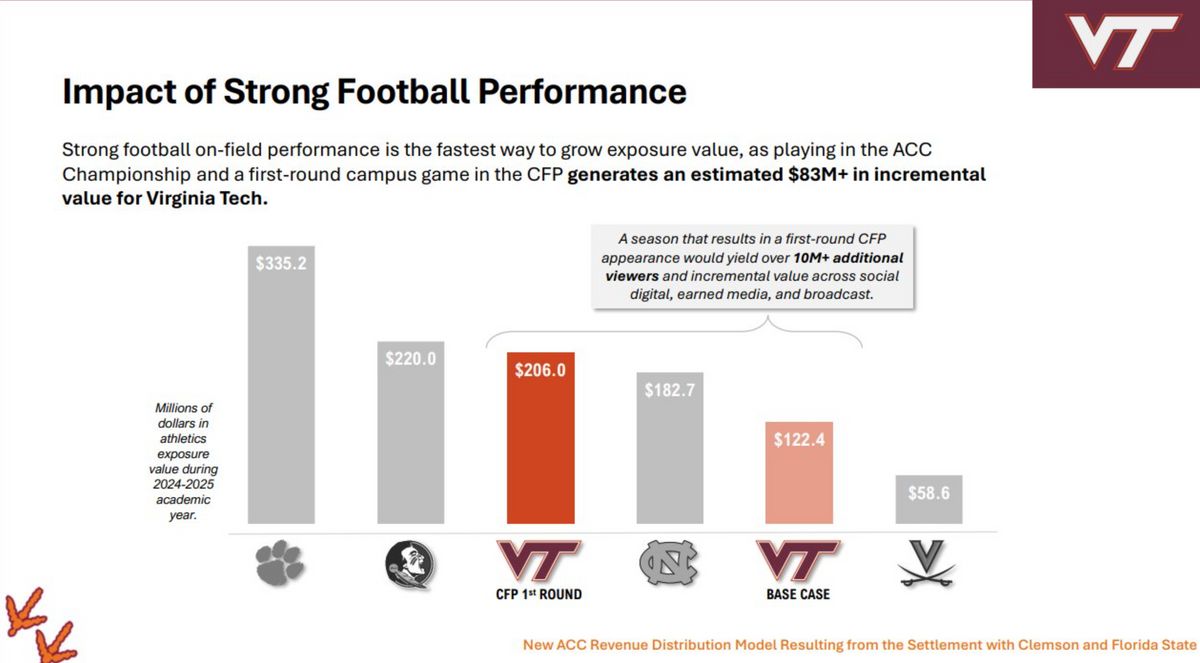

When 60 percent of your income is tied to TV ratings, this chart becomes a massive problem.

As stated above, Virginia Tech has picked a bad time to have a bad time. How does Babcock see Virginia Tech improving? By spending more money.

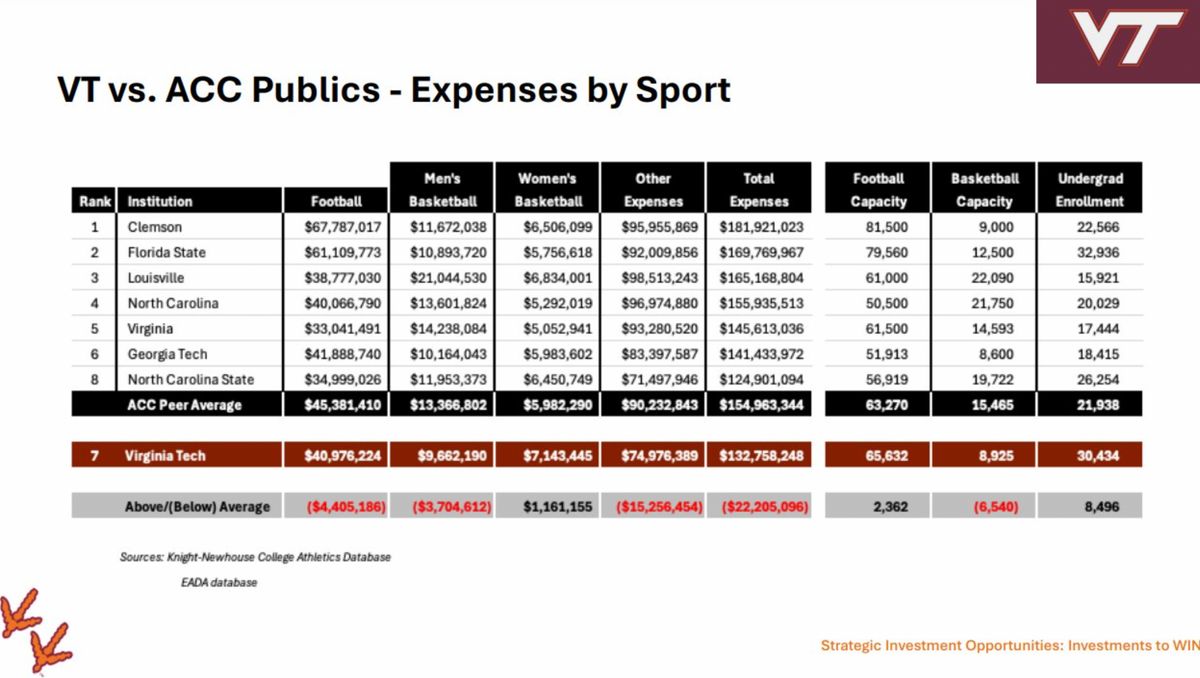

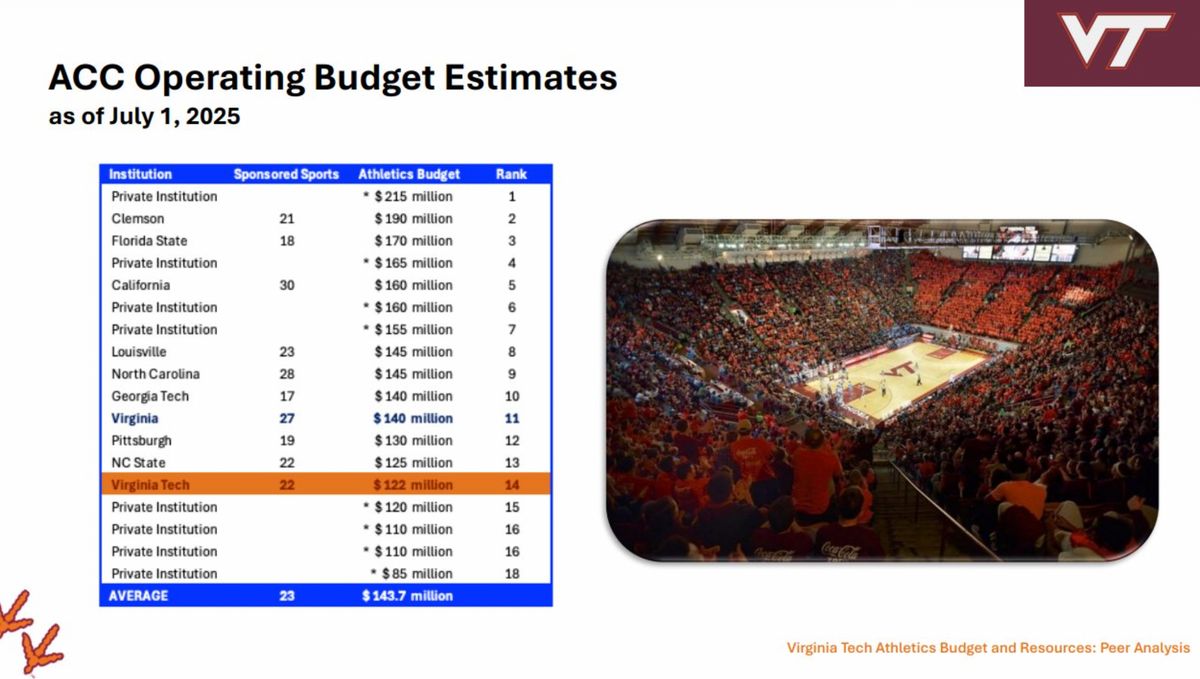

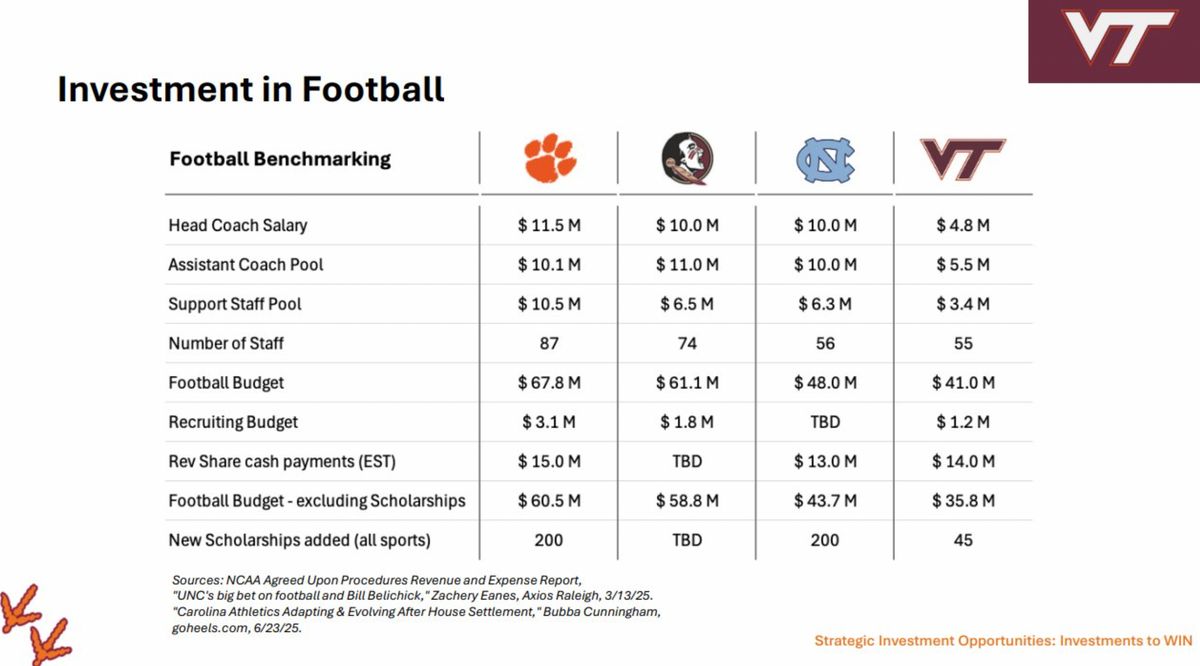

Virginia Tech spends, on average, $22 million less than its peers on athletics, and $5 million less on football.

The slides, which are far too numerous to reproduce here, included ways in which Virginia Tech has fallen behind, including somehow having an indoor facility that cannot be used year-round. It would take a one-time $8 million payment to add central air and heating to the 10-year-old Beamer-Lawson Indoor Practice Facility. To be honest, I didn't know such a thing was possible.

The carrot at the end of Babcock's stick will be this slide, showing that a Playoff-bound season would be worth $83 million in "estimated incremental value" for Virginia Tech.

How did Babcock and his staff come up with that $206 million figure? How do those "incremental" dollars replenish the very-real ones Virginia Tech will have to spend to them? Those are questions I'd have for Babcock were I a Virginia Tech visitor.

And if I was Babcock, I'd respond that, in recent years, Virginia Tech has been getting the results it's paid for.